The Role of Legal Framework and Market Structure

Market prices convey information about the value of the good or service traded. The Journal of Water tracks pricing in many areas of the west, including California, Colorado, Nevada, New Mexico and Texas. It is commonplace to use prices as an indicator of the economic value of water. However, one must sharpen their reasoning. Prices convey information about the value of water within (a) the legal framework of the underlying water right and (b) the structure of the market.

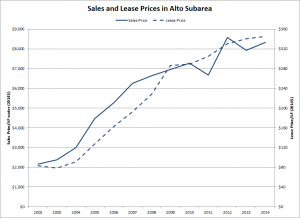

The market for leasing of water and sale of groundwater rights under the Mojave River Basin Adjudication provides an excellent case study. Through our predecessor publication Water Strategist and proprietary research, we have been tracking the price of leased water and water rights in the Alto Subarea of the Mojave River Basin since 2002. As shown below (as well as in the Journal of Water biennial market indicator reports in January and July), the lease price of groundwater and the sales price of groundwater rights have been rapidly increasing. What are the key drivers? There are two:

- Rapidly increasing cost of replacement water

- Reduction in competition in the lease market from unused water rights

The first factor reflects the fact that (i) pumping can exceed groundwater rights by either paying a replacement water assessment or lease water from other groundwater rightholders, (ii) replacement water assessments drive water lease prices, and (iii) the cost of replacement water has been increasing rapidly over the period. The second factor reflects the development of a decentralized market structure, although there is still room for further improvement in the breadth and transparency of the market for water and water rights in the Mojave River Basin Adjudication.

The Mojave River Basin Adjudication

Groundwater rights in the Alto Subarea originate from the adjudication of groundwater rights in the Mojave River Basin. The adjudication divided the basin into five subareas in which groundwater rights were allocated and regulated. Within each subarea, the watermaster (Mojave Water Agency) determines the total “Free Production Allowances” (“FPA”) consistent with the hydrologic balance of the subarea (e.g., avoid groundwater overdraft). The total Free Production Allowances are allocated among producers based on the producer’s share of total “Base Annual Production” (“BAP”). A producer’s BAP is defined as the verified maximum annual production of groundwater during the five-year period 1986-1990 (the five-year period preceding the initiation of legal proceedings that culminated in the Mojave Adjudication). The producer must replace all water produced in excess of its FPA either by making a payment to the watermaster with funds sufficient to acquire replacement water or by acquiring unused FPA from other producers.

To maintain proper water balances in the subareas, the Judgment provides for declining Free Production Allowances expressed as a percentage of total Base Annual Production. For municipal water use in the Alto Subarea, the ratio of FPA to BAP was 80% in 2002, declining by five percentage points annually until it reached 60% by 2006. Since that time, the ratio has remained constant. Therefore, a BAP in 2002 yielded 0.80 of a FPA in 2002, 0.75 of a FPA in 2003, and so on until it reached 0.60 of a FPA by 2006 and thereafter. To express the sales price of a BAP in terms of available water, one divides the BAP price in a year by the ratio of FPA to BAP in a year.

Sales and Lease Prices

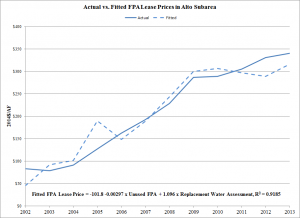

A leasing and sales market has developed in the Alto Subarea (see figure below). The lease price for an FPA (right to pump an acre-foot of groundwater without replacement water assessment) increased from $83/AF (2014$) in 2002 to $345/AF (2014$) in 2014. This equates to a cumulative annual rate of increase of 12.6% (in inflation-adjusted dollars!) over this time period. The sales price of a BAP (adjusted by the ratio of FPA to BAP) increased from $2,150/AF (2014$) in 2002 to $8,333/AF (2014$) by 2014. This equates to a cumulative annual rate of increase of 12.0% (in inflation-adjusted dollars!) over this time period.

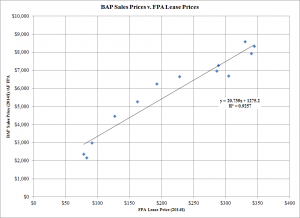

Prices of groundwater rights are related to lease prices (see figure below). For each one-dollar increase in the real lease price, the real groundwater right price increases by $20.74. The annual variation in the real lease price in the Alto Subarea explains 92.6 percent of the annual variation in real groundwater right prices in the Alto Subarea.

From an economics perspective, the sales price of an underlying water right is related to the lease price for water. As shown above, a dollar increase (2014$) in the FPA lease price translates into a $20.74 (2014$) increase in the sales price of a BAP (adjusted by the yield of FPA from a BAP). This “valuation multiple” is consistent with an inflation-adjusted annual yield of 4.8% (1/20.74) on water rights.

Drivers of Lease Prices

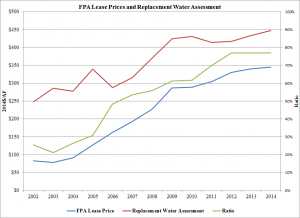

Knowing that lease prices drive water right prices, one’s attention naturally turns to the question what drives lease prices. For a party wanting to pump more than the Free Production Allowances available from their BAP rights, they have two alternatives: (a) pay the watermaster the replacement assessment on their excess pumping, or (b) lease FPA from a third party. Therefore, buyers in the leasing market would pay up to the replacement assessment for FPAs. On the other hand, sellers in the leasing market would make FPAs available if lease prices exceed the economic value to them from pumping groundwater. Therefore, one would expect that lease prices will follow the replacement water assessment but remain below the assessment.

FPA lease prices are below the replacement water assessment but they generally move together (see figure below). In the early years, FPA lease prices were 30% or less of the replacement water assessment. FPA lease prices then increased towards the replacement water assessment so that, for the last three years, FPA lease prices are just below 80% of the replacement water assessment.

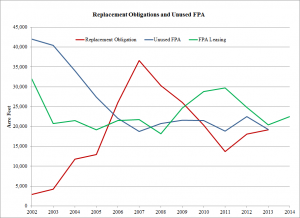

What gives? Well, there has been a significant decline in unused FPAs in the Alto Subarea (see figure below). “Unused” means that some groundwater right owners have more FPAs than needed for their own pumping or leasing activity. In 2002, there were about 42,000 AF of unused FPA. At the same time, some groundwater right owners pumped more groundwater than allowed under their own FPAs plus any FPAs leased. In 2002, the size of the replacement obligation was about 3,000 AF. The amount of unused FPAs fell by half within five years as the volume of replacement obligations increased twelve-fold. However, the volume of FPAs leased remained relatively stable after 2003.

Again, what gives? With leasing volumes stable, the decline in unused FPAs means that groundwater owners were using more of their FPA rights. The expansion in pumping must have reflected an increased economic value of groundwater. This, in turn, created upward pressure on FPA lease prices. The actual FPA lease price closely tracks a statistical model based on the amount of unused FPAs and the replacement water assessment (see figure below).

Market Structure

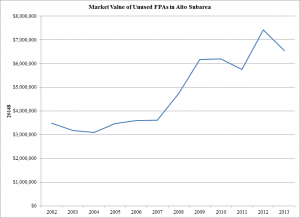

At first glance, it is remarkable that there is a significant volume of unused FPAs each year. As shown above, the volume of replacement water obligations now about equals the volume of unused FPAs. Individuals with unused FPAs are foregoing income by not leasing. Valuing the unused FPAs at the FPA lease price, groundwater owners were leaving almost $7 million (2014$) on the table in 2014 (see figure below).

This is a consequence of market structure. The transactions in FPA leasing and BAP rights is a decentralized, negotiated market. As in other water markets in the west, there will be a few brokers who help facilitate transactions. For a municipality seeking to lease FPA rights or purchase BAP rights, they or their representatives must find and “knock on the doors” of potential sellers. Alternatively, potential sellers must find and knock on the doors of potential buyers. As transactions are negotiated, each side is wondering how the prices they are discussing compare with other transactions under negotiation, many of which they may be unaware of. The “costs of transacting” may be substantial relative to potential gains. While it may be uneconomic to arrange smaller transactions, the group of small blocks can be significant in total.

What is needed is a centralized exchange where potential buyers and sellers can interact in a transparent way and prices that are fair to buyers and sellers. With such an exchange in place, the volume of unused FPAs should further decline. The entry of more FPAs into the leasing market will allow more buyers with replacement water obligations to cover themselves in the “cheaper” leasing market. As shown by the history of the Alto Subarea, the expansion of the marketplace will increase lease prices but they will remain below replacement water assessments.

Concluding Thoughts

Come full circle. The prices in water markets reflect the value of the right traded. In an adjudicated groundwater basin, such as the Mojave River Basin Adjudication, FPAs allow a right owner to pump groundwater without a replacement water assessment obligation. As a result, the prices of FPAs are driven by the cost of replacement water. FPA lease prices, in turn, drive the sales price of BAP rights.

It is interesting that significant blocks of FPA rights are not used or leased by right owners. They are consistently leaving money on the table. However, their plight reflects market structure rather than poor management. Decentralized, negotiated markets are a series of “one-off” deals. Market reconnaissance can help provide information about pricing in other transactions, but the search process is costly. Lacking a centralized exchange, a series of bi-lateral negotiations even in a competitive setting will inevitably leave “money on the table” for both the right owner who ends up with unused FPAs and the water user who pays replacement water assessments because they could not find a party with unused FPAs.

There is a solution. Stay tuned.

Written by Rodney T. Smith, Ph.D.

You must be logged in to post a comment.