Market prices provide valuable information about the economic value of water and water rights. What is the economic value of water this year in a designated area? Prices prevailing in an active lease market for water in the area can provide an answer. What is the economic value of water rights? Again, prices prevailing in an active market in the water rights can provide an answer. After all, the belief that market prices convey useful information is a central motivation for the Journal of Water researching transactions in western water.

Water markets are commonly informal networks characterized by small trading volumes. Large blocks of water rights are rarely traded. So, what happens when a large block of water rights becomes available? Do they sell at the same price as the small-volume transactions? Does the large block command a premium or sold at a discount?

In 2012, a bankruptcy auction involving 5,971 acre feet of Base Allocation Production (“BAP”) rights in the Alto Subarea of the Mojave Adjudication in Southern California’s high desert provides an answer: a large block of water rights commanded a premium.

Market Background

Groundwater rights in the Alto Subarea originate from the adjudication of groundwater rights in the Mojave River Basin. The adjudication divided the basin into five subareas in which groundwater rights were allocated and regulated. Within each subarea, the watermaster (Mojave Water Agency) determines the total “Free Production Allowances” (“FPA”) consistent with the hydrologic balance of the subarea (e.g., avoid groundwater overdraft). The total Free Production Allowances are allocated among producers based on the producer’s share of total “Base Annual Production” (“BAP”). A producer’s BAP is defined as the verified maximum annual production of groundwater during the five-year period 1986-1990 (the five-year period preceding the initiation of legal proceedings that culminated in the Mojave Adjudication). The producer must replace all water produced in excess of its FPA either by making a payment to the watermaster with funds sufficient to acquire replacement water or by acquiring unused FPA from other producers.

To maintain proper water balances in the subareas, the Judgment provides for declining Free Production Allowances expressed as a percentage of total Base Annual Production. For the Alto Subarea, FPA have equaled 80% of BAP for agricultural users and 60% of BAP for municipal users since 2006.

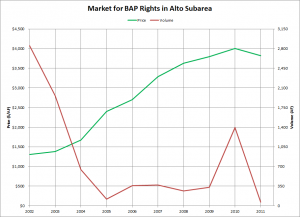

There are three types of transfers involving BAP rights: (1) purchase of rights, (2) inclusion of BAP rights in real estate transactions, and (3) administrative transfers. Water Strategist began tracking transactions of the BAP in 2002. The figure below plots the prices (weighted average price for transaction in a year) and volumes of transfers involving the outright sale of BAP rights by year through 2011 to represent the information available at the time of the bankruptcy auction. Prices for BAP rights increased from $1,305/AF in 2002 to $3,817/AF through 2011. The cumulative annual increase in BAP price was 12.7% from 2002 through 2011, although prices were increasing faster before 2008 (annual rate of 18.6%) than after 2008 (annual rate of 1.7%). The volume of outright sales of BAP rights was the highest in the early years.

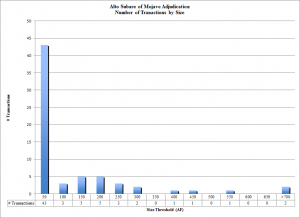

This market is mostly small-sized transactions—about two-thirds of the transactions involve less than 50 AF of BAP rights (see figure). The largest transaction was for 1,766 AF of BAP rights in 2002.

The Auction

Rancho Las Flores was a real estate development that went bankrupt with 5,971 AF of BAP rights. The real estate development and water rights were sold at auction. The City of Hesperia submitted a bid for the water rights in tandem with a real estate developer who submitted a bid for the real property. The city bid $30 million for the BAP rights, or $5,024/AF, which was the winning bid. This price represented a 20.5% premium over the highest price ever paid in a transaction and a 32% premium over the weighted average of prices paid in 2011.

The Rancho Las Flores BAP rights represent about 5% of the total BAP rights in the Alto Subarea. This block represents at least a decade of average volume in this market. Therefore, the alternative to acquisition of the Rancho Las Flores block of BAP rights would be engaging in more than a decade of small-volume transactions to acquire a like amount of rights.

Time was not on the side of Hesperia. Due to growth, Hesperia’s groundwater pumping was exceeding the Free Production Allowances available under the city’s BAP rights. Hesperia was only partly able to cover the discrepancy through leases of FPAs from third parties. Therefore, the City had significant replacement water obligations to the Mojave Watermaster. Due to anticipated increases in water demand, Hesperia was facing ever larger replacement water obligations unless it acquired Rancho Las Flores water rights. At the eve of the auction, the annual replacement water assessment was $395/AF that was increasing at an annual rate of 10% over the prior five years. So, acquiring the Rancho Las Flores BAP rights avoided 3,582.6 AF (60% of 5,971 AF) of replacement assessments annually. The avoided annual replacement assessments was $1.4 million in 2011 with reasonable expectations of growing savings with further increases in replacement assessments in future years.

Hesperia, of course, had an alternative to the Rancho Las Flores block of BAP rights. It could have entered the market with their acquisition program. The annual volume of BAP rights sold outright averaged about 850 AF. If Hesperia attempted to acquire 5,971 AF of BAP rights, this would represent a six-fold increase in volume. Would anyone reasonably anticipate that BAP prices would have remained firm around $4,000/AF? Hardly.

Conclusion

Market prices provide valuable information about the economic value of water and water rights. At the same time, one must consider the context of the transactions in the marketplace. Valuations of a large block of water rights based on market prices prevailing in small volume transactions would understate the economic value of a large block. Economic forces prevailing in small volume transactions are not strictly comparable for large blocks.

Written by Rodney T. Smith, Ph.D.

You must be logged in to post a comment.