On May 14, 2018, California through its Regional Water Quality Control Board, San Diego Region, and California Attorney General provided a 60-Day notice letter to Acting United States Commissioner to the International Boundary Water Commission (“USIBWC”) and Administrator of the Environmental Protection Agency (“EPA”) of the intent to sue USIBWC for violating the federal Clean Water Act. The controversy involves uncontrolled sewage flowing from Tijuana into San Diego County.

California’s Complaints

The dispute involves operations at the South Bay International Water Treatment Plant (“SBIWTP”), a secondary treatment plant owned by USIBWC built pursuant to Minute 283 of the 1944 Treaty between the United States and Mexico. Build in 1996, the SBIWTP was the first action to address significant cross-border flows of untreated sewage and pollutants. The National Pollution Discharge Elimination System permit issued by EPA covers the SBIWTP, five canyon collectors, two pump stations, the South Bay Land Outfall, South Bay Ocean Outfall and other associated infrastructure.

The system is designed to manage sewage flows during “dry weather” flows. When flows do not exceed the maximum design capacity of canyon collectors, properly maintained and operating collectors divert the flows to the SBIWTP for treatment and disposal through the South Bay Ocean Outfall. Any flows more than operating capacity of collectors continue flowing north to the border into the Tijuana River Estuary and the Pacific Ocean in the United States. These sewage flows result in beach closures at the cities of Imperial Beach and Coronado and interfere with Naval Training exercises.

California’s letter states eleven days of violations between April 19, 2015 and October 19, 2017 self-reported by the USIBWC. Spills totaled 11.86 million gallons. In three instances of spills, California alleges that USIBWC failed to collect samples and monitor for specific water quality parameters. On February 27, 2018, a spill of approximately 54,000 gallons of waste, including untreated sewage, occurred at one of the collector systems (Goat Canyon) due to a temporary power outage. California also complains that USIBWC failed to implement required response plan to (1) control or limit the spill or transboundary wastewater flow volume, (2) terminate the spill or transboundary wastewater flow volume, and (3) recover as much of the spill or transboundary wastewater flow volume for proper disposal.

Anatomy of The Tijuana Sewage Challenge

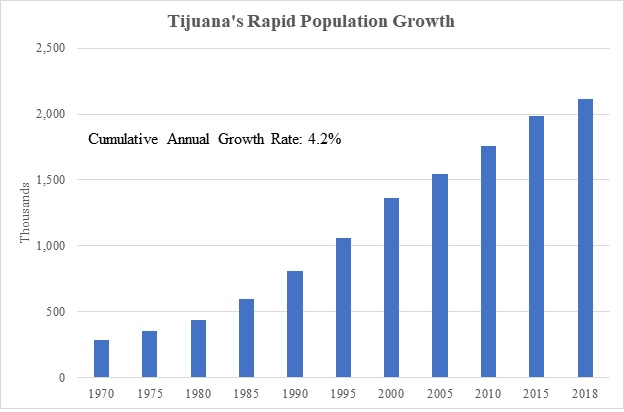

A half century of rapid population growth in Tijuana has overrun an aged and inadequate infrastructure (see figure for population growth, Source: World Population Review, http://worldpopulationreview.com/world-cities/tijuana-population/). Despite growth and development, poverty remains widespread as migrants from the South who live in extreme poverty are part of Tijuana’s rapid population growth.

Tijuana water users face a significant ability to pay challenge. The United Nations General Assembly has recognized a human right to clean drinking water and sanitation. This human right includes that water and sanitation be affordable—water and sanitation costs should not exceed 3 percent of household income (See United Nations, International Decade for Action “Water For Life”, http://www.un.org/waterforlifedecade/human_right_to_water.shtml.) An ability to pay based on 3 percent of Baja’s household incomes provides a modest economic foundation for infrastructure investment. The average household disposable income in Baja in 2014 is $8,682 in US dollars (Source: INEGI (Instituto Nacional de Estadistica y Geografia, http://www.beta.inegi.org.mx/app/bienestar/?ag=02#grafica). Applying the United Nation’s criterion for affordability of water and sanitation, the ability to pay of Tijuana’s households is $260 per year (3% $8,682), or about $22 per month.

There are two critical aspects of the Tijuana sewage system that have a bearing on cross-border sewage flows. First, experts estimate that perhaps half of residences are not hooked up to the sewage system. Sewage from unhooked-up residences flow into Tijuana’s stormwater system. Second, sewage flows and stormwater flows are comingled. During “wet conditions” high flows on the Tijuana River include high sewage loads crossing into the United States because the SBIWTP shuts down operations. With a treatment capacity of 25 million gallons per day, shutting down the plant during wet conditions contributes to the flow of sewage into the United States.

Finding Solutions

There are other initiatives seeking to address the Tijuana sewage issue. The Binational Core Group established in 2015 under Minute 320 is charged with identifying projects that address pollution and sediment issues in the Tijuana River Valley basin. The North American Development Bank is funding a feasibility study (“Tijuana River Diversion Infrastructure Study”) to provide a diagnosis of transboundary flows in the San Diego region. The study will identify potential operational improvements and infrastructure upgrades in both the United States and Mexico. This study is expected to be completed this December.

Finally, the Mexican non-governmental organization Tijuana Innovadora has launched the Tijuana Verde Citizen Observatory Initiative. The objective is to provide a framework for forming a regional consensus on sewage projects and programs on both sides of the border. A proposed website will be a valuable tool for providing transparency and credible information on sewage problems and solutions. The proposed public outreach program will provide a forum for public discourse and input for studies and projects sponsored by US, Mexican or binational entities, including the North American Development Bank. A proposed technical committee will provide third-party, peer review of studies and projects. Tijuana Verde supports development of funding mechanisms that reflect legal responsibilities of parties, rate-payers ability to pay and the economic benefits created by solving sewage issues in the region.

Written by Rodney T. Smith, Ph.D.

Editor’s Note: The author is assisting Tijuana Innovadora develop the Tijuana Verde Citizen Observatory Initiative and is a member of its Technical Assistance Committee

You must be logged in to post a comment.